PAKISTAN HISTORY

BACKGROUND TO PARTITION

The Muslim League and Mohammed Ali Jinnah. The movement among the Muslim population of the India-Pakistan subcontinent that culminated in the creation of Pakistan stemmed from the historical fact that, for more than six centuries before the effective domination of the; British in India, Muslim soldiers and administrators had)i controlled a population in which Hindus were a numerical majority, although mass conversions to Islam in economically backward areas like East Bengal (Bangla desh) produced local Muslim majorities. When the British replaced Muslim domination by their own, the tradition of rule prevented the Muslims from adapting themselves to the new situation as readily as the Hindus; but the failure of the risings of 1857 dashed Muslim hopes of a restoration of their authority. Later, while Hindus were pressing for constitutional reform through the Indian National Congress, the Muslims sought various guarantees to safeguard their minority position and finally founded their own political organization, the All-India Muslim League, at Dacca in 1906. For a more complete discussion of Pakistan under British rule and the history of Pakistan before British domination .

The gradual clarification of the British intention to grant self-government to India along the lines of British parliamentary democracy aroused Muslim apprehensions regarding ultimate political subjection to the Hindu majority of the population. Mohammed Ali Jinnah, as eager as any Hindu nationalist to bring British rule to an end, was at length driven to the conclusion, which the renowned poet-philosopher Muhammad Iqbal had already expressed, that the only way to preserve Indian Muslims from complete political, economic, and cultural subordination to the Hindus was to establish a separate Muslim state. By 1940, the demand for Pakistan had been formally endorsed by the Muslim League under his leadership.

British policy, supported by the whole weight of the Hindu nationalist movement, labored hard to avoid disrupting the economic and political unity built up during the period of British rule. None of the many suggested alternatives to separation of Pakistan commended them-selves to Jinnah, whose leadership of the bulk of the community was unchallenged, and without his cooperation- of which the price was Pakistan-Indian independence was impracticable. His courage and implacable determination triumphed in the end.

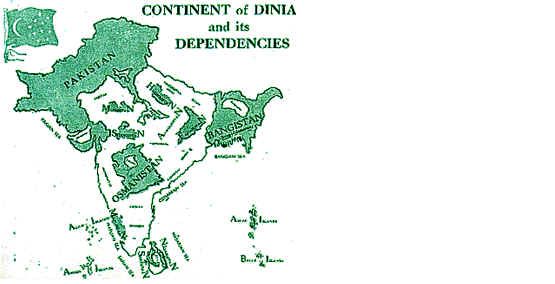

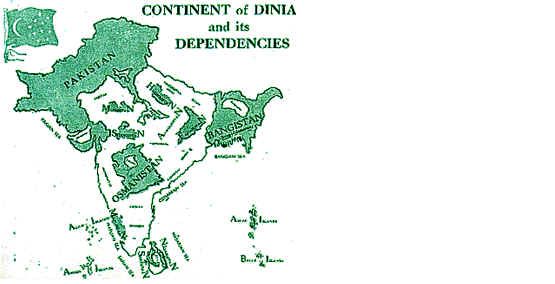

Birth of the new state. The new state came into existence as a dominion within the Commonwealth in August 1947, with Jinnah as its first governor general and his ablest colleague, Liaquat Ali Khan, as its first prime minister. With West and East Pakistan separated by more than 1,000 miles of Indian territory, and with the major portion of the wealth and resources of the British heritage passing to India, Pakistan's survival seemed to hang in the balance. Of all the well-organized provinces of British India, only the comparatively backward areas of Sind, Baluchistan, and the North-West Frontier came to Pakistan intact. The Punjab and Bengal were divided, and Kashmir became disputed territory. Economically, the situation seemed almost hopeless; the new frontier cut off Pakistani raw materials from the Indian factories, disrupting industry, commerce, and agriculture. The partition and the movement of refugees were accompanied by terrible massacres for which both communities were responsible. India remained overtly unfriendly; its economic superiority expressed itself in a virtual blockade. The dispute over Kashmir brought the two countries to the verge of war; and India's command of the headworks controlling the water supplies to Pakistan's eastern canal colonies gave it an additional economic weapon. The resulting friction, by obstructing the process of sharing (according to plans previously agreed) those assets inherited from the British raj, still further handicapped Pakistan in solving its problems.

ISLAMIC REPUBLIC OF PAKI5TAN

India, too, received the advantage of Jawaharlal Nehru's leadership for almost two decades; Mohammed Ali Jinnah, however, died in September 1948, within 13 months of independence. The leaders of the new Pakistan were mainly lawyers, with a strong commitment to parliamentary government. They had supported Jinnah in his struggle against the Congress not so much because they desired an Islamic state as because they had come to regard the Congress as synonymous with Hindu domination. They had various degrees of personal commitment to Islam. To some it represented an ethic that might (or might not) be the basis of personal behavior within a modern, democratic state. To others it represented a tradition, the framework within which their forefathers had ruled India. But there were also groups that subscribed to Islam as a total way of life, and these people were said to wish to establish Pakistan as a theocracy (a term they repudiated). The members of the old Constituent Assembly, elected at the end of 1945, assembled at Karachi, the new capital.

Jinnah's lieutenant, Liaquat Ali Khan, inherited the task of devising an acceptable formula. Himself a moderate (he had entered politics via a landlord party), he sub-scribed to the parliamentary, democratic, secular state. But he was conscious that he possessed no local or regional power base. He was a "refugee"; he came from the United Provinces, the Indian heartland, whereas most of his colleagues and potential rivals drew support from their own people in Punjab or Bengal. Liaquat Ali Khan therefore deemed it necessary to gain the support of the religious spokesmen (the mullahs or, more properly, the 'ulama). He issued a resolution on the aims and objectives of the constitution, which began, "Sovereignty over the entire universe belongs to Allah Almighty alone" and went on to emphasize Islamic values. This led to protests from Hindu members of the old Constituent Assembly; Islamic states had traditionally distinguished between the Muslims, as full citizens, and dhimmis, nonbelievers who were denied certain rights and saddled with certain additional obligations.

Political decline. Liaquat Ali Khan fell to an assassin's bullet in October 1951. Into his place as prime minister stepped Khwaja Nazimuddin, the leading member of the family of the Nawab of Dacca. He was a Bengali aristocrat and a man of extreme personal piety. Nazimuddin had followed Jinnah as governor general under the interim constitution (virtually the 1935 Government of India Act). He was succeeded as governor general by Ghulam Mohammed, a Punjabi, so that the twin pillars of power represented the two main regional power bases in West Pakistan and East Pakistan.

With Nazimuddin in office, militant Muslims, led by the Ahrars, a puritanical political group, called for the purification of national life. In 1953 they demanded that the Ahmadiyah sect should be outlawed from the Islamic community. Nazimuddin temporized, and rioting and arson enveloped Lahore and other Punjabi towns. The secretary of defense, Col. Iskander Mirza, a former political officer, pressed the Cabinet into sanctioning the promulgation of martial law in Lahore, and order was restored. Ghulam Mohammad decided that Nazimuddin must go, although he enjoyed the support of the Constituent Assembly. The dismissal was effected, and a new prime minister from Bengal was found in Mohammad Ali Bogra.

Without a constitution, the legislative assemblies, both national and provincial, were replenished ad hoc. But in March 1954 a general election was held in East Bengal (East Pakistan) to choose a new provincial legislature. The contest was between the official Muslim League and a "United Front" of parties from the extreme right (orthodox religious) to extreme left (quasi-Marxist). There was a landslide defeat for the Muslim League. At the head of the victorious opposition stood two politicians who had previously kept one foot in the Muslim League and the other in the camp of the Congress and regional politics; these were the aged Fazl ul-Haq, with his Krishak Sramik (Workers and Peasants) Party, and Hussein Shaheed Suhrawardy, with a new party, the Awami League. The result was a dramatic demonstration of the gulf between West and East Pakistan.

THE CONSTITUTION OF 1956

The Constituent Assembly reflected the new political mood by attempting to curb the powers of the governor general, who retaliated by proclaiming the dissolution of that body. Ghulam Mohammad's action was validated by the Supreme Court, with the rider that a new assembly must be convened. This was produced by a system of indirect election. The ministry of Mohammad Ali Bogra was completely reorganized, with three newcomers introduced as strong men from outside politics: these were Maj. Gen. Iskander Mirza, as minister of the interior, Gen. Mohammad Ayub Khan, commander in chief, as minister of national defense, and Chaudhri Mohammad Ali, a senior civil servant, as minister of finance. Mohammad Ali Bogra had little support in the new assembly, and he was replaced by Chaudhri Mohammad Ali.

Ghulam Mohammad, whose health had broken down, was replaced as governor general in August 1955 by Iskander Mirza. The latter had no regional power base and little in common with any of the politicians. Mirza insisted that his fellow administrator Chaudhri Mohammad Ali remain prime minister, and Chaudhri was able to succeed in one objective over which his three predecessors had failed: he induced the politicians to agree to a constitution (February 1956). In order to create a better balance between the West and East wings, the provinces and parts of West Pakistan were amalgamated into one administrative unit. The constitution of 1956 embodied the Islamic provisions of the "aims and objectives" resolution of 1949 and declared Pakistan to be an Islamic republic. The national parliament was to comprise one house of 300 members, equally representing East and West. Ten seats were re-served for women. In constitutional theory the prime minister and Cabinet were to govern according to the will of the parliament, with the president exercising only reserve powers.

Khan Sahib, a former premier of North-West Frontier Province, was invited by the Muslim League to become the chief minister of the new "one unit" of West Pakistan. Soon after taking office, Khan Sahib was faced with a revolt against his leadership in the Muslim League, but he adroitly turned the tables by forming a new group, the Republican Party, out of dissident Muslim League assemblymen. In the National Assembly also, members adopted the Republican ticket, and Prime Minister Chaudhri Mohammad Ali found himself without a majority. He re-signed in September 1956.

Iskander Mirza, then president, was compelled to accept an Awami League government headed by Suhrawardy but dependent on Republican support to retain office. For a time the combination worked, but the flimsy consensus of Pakistan politics soon began to dissolve into factionalism, regionalism, and sectarianism. Khan Sahib found his hold over the West Pakistan legislature slipping, and he asked the President to suspend the constitution. The East Pakistan legislature voted unanimously for autonomy in all matters except foreign affairs, defense, and currency. The country was to hold its first complete general election in 1958, but a dispute over the basis of the constituencies led to Suhrawardy's resignation. His successors proved ineffective, and the legislative process came to a halt.

Military government. President Mirza had made no secret of his dissatisfaction with the working of parliamentary democracy in Pakistan. He therefore came to a decision to put an end to politics. On October 7, 1958, a presidential proclamation announced that the political parties were abolished, the constitution abrogated, and the country placed under martial law, with Gen. Mohammad Ayub Khan as chief martial law administrator. Mirza announced that the martial law period would be brief and that a new constitution would be drafted. On October 27 he swore in his new Cabinet.

MOHAMMAD AYUB KHAN

General Ayub became prime minister, and three lieutenant generals were named to the Cabinet. The eight civilian members included businessmen and lawyers, one being a young newcomer, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto. That same evening the new military ministers called on the President, with contingents of armed soldiers, and informed him that he was to resign. After a short interval, Mirza was exiled to London. A proclamation issued by Ayub announced his assumption of the presidency.

Martial law lasted 44 months. During that time a number of army officers took over vital civil-service posts. A number of politicians were excluded from public life under the Electoral Bodies (Disqualification) Order, or EBDO. A similar purge took place among civil servants.

Ayub had long pondered the problem of creating political institutions that would express Islamic ideals and foster national development. He came forward with a plan for "basic democracies," directly elected by the people, as local units of development. Elections for the basic democracies took place in January 1960. The Basic Democrats, as they became known, were at once asked to endorse Ayub's presidency and to give him a mandate to frame a constitution. Of the 80,000 Basic Democrats, 75,283 gave him affirmative votes (February 1960). A constitutional commission was asked to advise on a suitable form of government. Ayub accepted some of its proposals and substituted some of his own, aiming, he said, for "a blending of democracy with discipline." In the early days of Ayub's regime there were notable reform measures, such as the Muslim Family Laws Ordinance of 1961, restricting polygamy, but later the President found it necessary to make concessions to Muslims in order to bolster his regime.

One feature of the Ayub regime was the quickening pact! of economic growth. During the initial phase of independence, the growth rate was less than 3 percent per annum and scarcely moved ahead of the rate of population growth. During the mid-1950s even this rate declined, but from 1960 to 1965 the rate advanced to more than 6 percent per annum. Development was particularly vigorous in the manufacturing sector.

There was considerable imbalance between East and West; during the 1950s East Pakistan was becoming poorer in per capita terms every year, whereas the West was achieving positive growth. A continuing grievance was the contribution made by East Pakistan to foreign exchange{ by the export of jute and tea, from which it was felt the West reaped more advantage; the West was also the major beneficiary of foreign aid.

The outstanding example of favoured treatment for the West was the great Indus Basin scheme for hydroelectric development. Pakistan skillfully negotiated for assistance from the World Bank, the United States, and other friends.; In addition to economic aid, Pakistan also received immense military aid from the United States.

The war over Kashmir in 1965 had more far-reaching effects on Pakistan than on India. Ayub received a new mandate from the Basic Democrats in January 1965, when he won decisively against a spirited challenge from Fatima Jinnah, the sister of Mohammed Ali Jinnah. In the early days of his presidency Ayub had moved freely among the rural people, talking to them face to face. After the war he withdrew behind a curtain of dictatorship, becoming a remote figure in a bulletproof limousine. Bhutto, the chief exponent of struggle against India, was relieved of office in 1966. Mujibur Rahman (Sheikh Mujib), who had inherited the leadership of the Awami League, the major force in East Pakistan, was arrested and accused of conspiring with India.

Ayub's autocratic position was suddenly challenged in the autumn of 1968; an unsuccessful attempt on his life was followed by the arrest of Bhutto and other opposition leaders. Ayub attempted to stem the mounting protest by summoning a conference of opposition leaders and by withdrawing the state of emergency under which Pakistan had been governed since 1965. These concessions failed to conciliate the opposition, and in February 1969 Ayub announced that he would not contest the presidential election due in 1970. Protests and strikes flared everywhere, being especially militant in Bengal. At length, on March 25, 1969, Ayub resigned, handing over responsibility for governing to the commander in chief, Gen. Agha Mohammed Yahya Khan. Once again the country was placed under martial law. Yahya assumed the title of president as well as chief martial law administrator. He made it clear that his aim was an early general election, which took place in December 1970.

Civil war. The success of the Awami League in East Pakistan surprised even its friends. Sheikh Mujib emerged with a majority at his command among the membership; of the new assembly (167 of the 300 total). But what upset all predictions was the victory in West Pakistan of Bhutto's Pakistan People's Party (PPP), which won particularly heavily in Punjab and gained a clear majority (83) of the representation from the West. Yahya's plan provided that when the new assembly met it must produce a constitution within 100 days. Mujib, however, stood out for complete independence for East Pakistan, except for foreign policy, though the East wanted to make its. own aid, trade, and defense agreements. Bhutto rejected these terms and refused to bring his party to Dacca to participate in the assembly. On March 1, 1971, President Yahya announced that the National Assembly would be suspended indefinitely. Sheikh Mujib replied by ordering a boycott and general strike throughout East Pakistan. Bowing to the inevitable, Yahya proceeded to Dacca in mid-March to negotiate a compromise that would concede the substance of Mujib's demands while retaining tenuous ties that might still preserve the name of Pakistan. But compromise proved impossible. President Yahya denounced Mujib and his men as traitors and launched a drive to "reoccupy" the East with West Pakistan troops.

Warfare between government troops and supporters of the Awami League broke out in the East in March. Sheikh Mujib and many of his colleagues were arrested, while others escaped to India, proclaiming East Pakistan an independent state under the name Bangladesh (Bengal Land). As fighting continued, the number of refugees crossing the border into India grew into the millions. In December 1971 India successfully invaded East Pakistan. The establishment of a Bangladesh government with Mu-jib as prime minister followed in January 1972.

Bhutto's regime. Accepting responsibility for the defeat and breakup Of Pakistan, President Yahya resigned on December 20, 1971, and Bhutto became the undisputed leader of former West Pakistan. He secured another election victory for the ppp, opposition being largely confined to the North-West Frontier Province and Baluchistan, where the National Awami Party (NAP) demonstrated support for its autonomy program. Bhutto's declared policy of Islamic Socialism brought few tangible changes, but his populism was undeniably successful. He became increasingly autocratic, however, suppressing criticism, jailing opponents, and employing militant methods against the restive Pashtuns and Baluchs. A new constitution was adopted on April 10, 1973, and Bhutto became prime minister of Pakistan.

On January 4, 1977, Bhutto announced that elections would be held within two months, unfolding a national charter of peasant reform. Nine opposition parties hastily patched together the Pakistan National Alliance (PNA) and launched a demand for the Islamic way of life in Pakistan. The campaign was marked by violence, with opposition candidates complaining of brutal discrimination. The re-suits were a sweeping victory for Bhutto's PPP, which obtained 155 of the 200 seats in the legislature.

The results were denounced as fraudulent by the PNA. Mounting protest soon brought chaos to Karachi and other major cities, where Bhutto was compelled to call out the army and proclaim martial law. He tried to buy peace by offering concessions to the PNA leaders (most of whom were under arrest), but they would accept nothing short of a new election. Religious leaders (maulvis) declared that Bhutto was an unlawful ruler whom it was no crime to kill.

Zia ul-Haq's regime. To avoid total chaos, the chief of staff of the army, Gen. Mohammad Zia ul-Haq, took over as chief administrator of martial law on July 5, 1977. His early efforts to create an acceptable political alternative had only limited success. He announced that elections would be held in 90 days, but it was clear that Bhutto was the only politician of mass appeal. In September Bhutto was arrested and charged with attempted murder, and he was sentenced to death on March 18. Zia was proclaimed president of Pakistan on September 16.

By this time the PNA was split, with most elements forming an opposition that demanded early elections, withdrawal of the army from Baluchistan, and the introduction of a full Islamic code of laws. A zealous Muslim, Zia had already imposed Islamic criminal punishments, such as flogging and maiming, which were formally enacted as law in February 1979. Bhutto was hanged on April 4, 1979, following a Supreme Court review of his case. In October elections were postponed indefinitely, political parties and strikes were banned, and the press was submitted to strict censorship.

The invasion of Afghanistan by the Soviet Union in December 1979 became central to Pakistan's internal and foreign affairs. Claiming that a Soviet attack on his country was possible, Zia embarked upon a military buildup supported by the United States and by other Islamic countries and feared by India. The influx of millions of refugees from Afghanistan led Zia also to acquire foreign economic aid. On March 24, 1981, Zia announced a pro-visional constitutional order that allowed the government to be kept under martial law indefinitely and that gave the president power to amend the constitution. A 350-member Federal Advisory Council-whose members were nominated and had no decision-making powers-was established in December and held its first meeting on January 11, 1982. There were periodic outbursts of religious and political violence throughout the year. Against that background, Zia praised the armed forces and sought a role for them in the making of national and international policy.